THE SECRETS OF RECORD CUTTING

ABOUT CUTTING

The magic behind the groove

If you ask music fans how records are made, you'll usually hear: “They're pressed.”

But what almost no one knows is that before a record is pressed, it has to be cut.

This magical moment—when a needle digs into a shiny blank and transforms sound into material—is the origin of every vinyl record.

This is where the soul is created.

This is where we come in.

Our direct-cut device is the tool for this moment. For artists. For music lovers. For dreamers, doers, collectors.

Would you like to learn more?

TECHNIQUE OF RECORD CUTTING

What technical requirements are necessary?

In order to understand a record cutting device, it is necessary to understand its technical structure and the associated difficulties. The basic technical terms and their extensive interrelationships are summarized here.

The basic principle of mechanically engraving the acoustic signal into a solid material, as invented by Thomas Edison in 1877, is still used in record production today. What has changed are the materials being cut, the cutting processes, the technical implementations, and the methods of reproduction. This chapter presents the material and technical developments in these areas.

TOPICS

1. MATERIALS

2. ENGRAVING PROCESSES

3. TURNTABLE and PLATTER DRIVE

4. CUTTER HEAD

5. CUTTING CONCEPT

6. CUTTING STYLUS

7. STYLUS PRESSURE

8. HEATING (blank and stylus)

9. GROOVE SPACING and GROOVE DEPTH

10. SUCTION

11. AUDIO SIGNAL PROCESSING

12. POWER AMPLIFIER

13. MANUFACTURE OF INDIVIDUAL PIECES AND SMALL SERIES

14. PRODUCTION OF LARGE SERIES

15. DAW (Digital Audio Workstation)

16. DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter)

17. AUDIO INTERFACE

18. SIGNAL PATHWAYS

1. MATERIALS

In the first 100 years after the first phonograph was invented, there was a lot of experimentation and further development as technical capabilities increased. In the last 50 years, however, there had been no significant further development due to low demand for records since the 1980s. It is only in recent years that development research has been carried out again.

1.1. Sound carrier material

In the first Edison phonograph, a sheet of tin foil was stretched over a cylinder (tin foil). In its improved version, a cylinder with a wax coating was used, which could be duplicated initially by copying and later by casting, albeit a very costly process. In 1893, celluloid on a brass core was used for the cylinders.

In 1887, the first records were cut into a thick layer of soot applied to a glass plate. The chemical-galvanic reproduction of these blanks was easier and cheaper to produce than with cylinders. Subsequently, wax layers were also used for cutting records. The duplicated records were made of shellac.

In 1903, in collaboration with chocolate manufacturer Ludwig Stollwerk, edible chocolate was also used as a sound carrier.

After World War II, record production was further commercialized and, for the first time, marketed to wealthier customers as home recorders. Plastic-coated fiberboard was offered as blank media.

In the late 1950s, manufacturing was further developed through improved technologies. Stereo cutting was introduced and cut into a lacquer layer applied to an aluminum plate. Record pressing plants switched from shellac to vinyl. By 2020, 80% of the world’s lacquer blanks were manufactured by Apollo Masters in California. In February 2020, the Apollo Masters factory burned down. Due to a lack of alternatives, record production around the world has been affected.

Apart from Apollo Masters, the Japanese manufacturer MDC was now the only company that produces 14-inch discs with a lacquer coating.

The most advanced cutting process developed in the 1980s involved cutting into a copper plate, which greatly simplified the electroplating process for matrix production. This cutting process was called DMM (Direct Metal Mastering) and was considered the last major innovation.

In further, partly successful attempts, cuts were made in PVC, PETG plastic (and in Russia, to circumvent censorship in the 1960s, even on X-ray images).

Image: Vinyl records made from X-ray images

uses PET-G blanks for the FP9 direct-cut record cutting machine

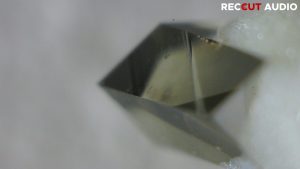

1.2. Material of the cutting stylus

Initially, the Edison phonograph used a blunt stylus to press the tin foil tape more or less deeply in accordance with the movement of the membrane. Although the spoken sounds were understandable, the sound quality was very poor and the cylinder could only be played a maximum of five times. In the more advanced wax cylinders, a pointed steel stylus was used to engrave the signal into the wax. From 1906 onwards, the first diamond styluses were used for the increasingly hard wax layers.

In the days of shellac records, the blanks (wax on tin plates) were also first processed with pointed steel styluses, tungsten needles, ruby or diamond styluses.

Other materials used were cutting needles made of steel, stellite, or sapphire. Stellite is the commercial name for hard alloys based on cobalt and chromium. Today, they are classified as non-ferrous alloys, but stellite with up to 20% iron by volume was also known in the 1950s.

From the production of vinyl records (after the Second World War), lacquer discs (aluminum discs with a special lacquer coating) were used almost exclusively as blanks for master cutting. Sapphire gravers were used to cut into the relatively soft lacquer material.

Direct cutting processes are used to produce small series. This avoids the costly process of electroplating and the record pressing plant. However, each record must be cut individually in real time, and the soft lacquer material of the lacquer blanks is unsuitable because it would be quickly destroyed by the stylus during playback and would also stick to the stylus. A resistant PETG or PVC material must therefore be used, as this is much harder and achieves the same durability as vinyl records when played. However, sapphire cutting styluses are only suitable for cutting in lacquer or for embedding (pressing), but not for cutting these plastics, as they are not hard enough. Only diamond styluses are suitable for cutting PVC or PETG. (The difference between embedding and cutting is described in the cutting concept section).

Image: SAPHIR Stylus with heating

uses a heated diamond cutting stylus type 320 for the CH9 cutting head

2. ENGRAVING PROCESS

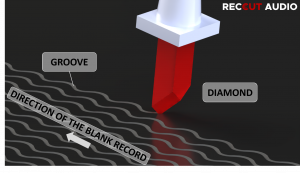

The engraving process describes the way in which acoustic signals are scratched, pressed, or cut into the medium.

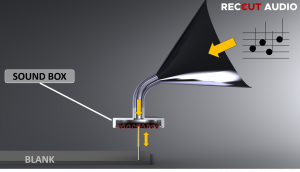

2.1. Vertical recording process

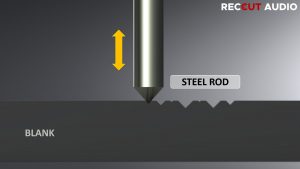

At the time of Thomas Edison’s invention of the phonograph in 1877, microphones did not yet exist, which meant that sound transmission had to be purely mechanical. Sounds are basically air vibrations that are picked up by the membrane in our ear, the eardrum. Based on this principle, the sounds were captured in a funnel and directed onto a sensitive membrane. A needle was attached to this membrane, which then carved a groove into a wax cylinder by moving up and down.

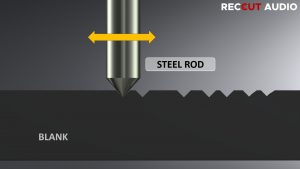

Figure: How the vertical recording process works using a funnel and membrane

The wax cylinder rotated and the needle was moved evenly along the cylinder. A pointed graver was used as the needle. The engraving was referred to as a deep-cut process because the sound frequencies (from above) were pressed more or less deeply into the blank. Loud sounds were pressed deeper into the material and quiet sounds less deeply.

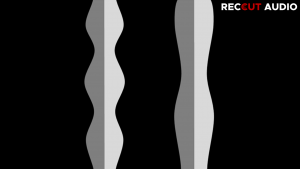

The illustration shows the (stylized) groove formation. Loud tones are cut deeper and therefore have a wider groove.

The groove formation on the left also shows a higher frequency than the groove on the right.

This principle was used not only in cylinder phonographs, but also in old gramophone records.

Figure: How the vertical recording process works using a funnel and membrane

Example of vertical recording on a record with different frequencies:

Figure: Groove formation in the vertical cut

2.2. Lateral recording method

The disadvantage of the vertical recording method was that the deeper the cut, the exponentially greater the force required. This quickly pushed the funnel and membrane to their limits.

The solution to the problem lay in the side-writing method (Lateral recording). Instead of going deeper, the signal was deflected sideways. The depth remained the same. This allowed for louder and better quality recordings.

Figure: How the lateral recording method works using a funnel and membrane

This process was used for almost all gramophone records. To improve quality, higher record speeds of 78 (exactly 78.26) revolutions per minute were chosen and a large deflection was sought. Larger diaphragms and larger horns were used for greater deflection. Initially, these were so large that they could no longer be moved over the turntable. Instead, the turntables were moved past the needle.

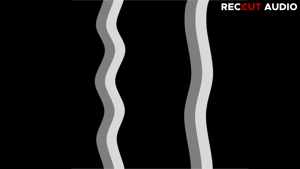

The illustration on the right shows the (stylized) groove formation. Loud sounds are cut further to the side and therefore require more space.

The groove formation on the left also shows a higher frequency than the groove on the right.

This principle was used not only for gramophone records, but also for old mono records.

Figure: Groove formation during the lateral recording method

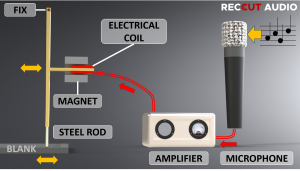

Following Graham Bell’s invention of the microphone in 1876, its further development into the carbon microphone by Georg Neumann in 1923, and the advent of electrical signal transmission, electromagnetic coil drives replaced the funnel and diaphragm.

Figure: How the lateral recording method works using electromagnetic drive

Example of lateral recording method on a vinyl record with different frequencies:

Figure: Groove formation during the lateral recording method

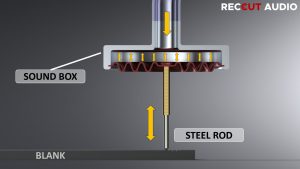

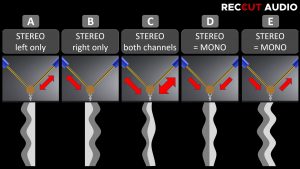

2.3. 45/45-type stereophonic recording

In the second half of the 20th century, there were several developments in the record industry. One was the introduction of polyvinyl chloride records, which replaced shellac records, and stereo sound reproduction. In order to keep costs low for customers, a system had to be found that allowed stereo record players to play mono records and mono record players to play stereo records (at least in mono).

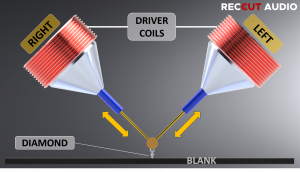

Accordingly, the 45/45-type stereophonic recording was introduced, which is a combination of the vertical and lateral recording method.

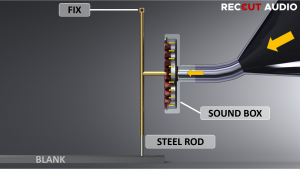

Figure: How the 45/45-type stereophonic recording works using electromagnetic drive coils

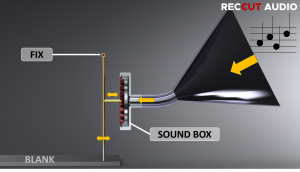

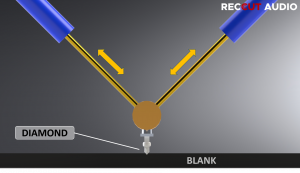

Two drive coils were used for implementation, each pressing a rod at a 45° angle onto the cutting tool and thus cutting the left and right channels separately (see image above).

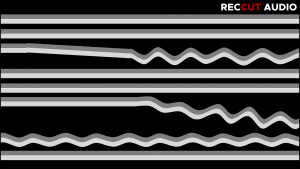

The following illustration shows various (stylized) groove formations.

In the first two cut images (A & B), only one channel was controlled (the cut goes diagonally downwards).

In the third cut image (C), both channels were controlled at different frequencies, resulting in a stereo image being cut.

The last two images are produced using the 45/45-type stereophonic recording method, but only reproduce a mono signal. This is because the same signal is applied to both channels. However, in the fourth groove image (D), the electrical signal is applied to both channels in phase, causing both drive rods to move up and down simultaneously, resulting in a depth recording image.

In the fifth groove image (E), a signal is reversed. This causes the two inclined drive rods to move in the opposite direction. When one rod moves upward, the other rod pushes downward, creating a side image. This polarity reversal method is still used today for mono recordings.

Figure: Different groove formations in the stereo side-writing process

A: Only the left channel is cut here.

B: Only the right channel is cut here.

C: Both channels are cut with different frequencies and volumes.

D: Both channels are controlled with the same signal and electrical current direction. The result corresponds to the MONO depth writing process.

E: Both channels are controlled with the same signal but different electrical current directions. The result corresponds to the MONO side-writing method.

uses the 45/45-type stereophonic recording for the CH9 cutting head

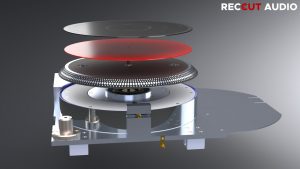

3. TURNTABLE AND PLATTER DRIVE

The first step in manufacturing a record is to cut an existing audio signal into a groove on a blank disc. Since the cutting process (and later also the playback process) is mechanical, physical limitations must also be taken into account. The design and precision of the components used are ultimately decisive for the sound quality of the end product.

In this chapter, we will take a closer look at the necessary components and introduce them in more detail.

The mechanical processing of the blank disc during pressing (embedding) or cutting (cutting) creates a braking torque. This is not uniform, but varies in intensity according to the changing audio signal. For example, high volumes and strong bass (low frequencies) can cut a deeper or wider groove, which causes a higher braking torque (see typefaces in the chapter on type processes).

The turntable drive must be correspondingly high-torque and insensitive to speed fluctuations. Alongside Scully, Neumann was the market leader in cutting machines from the 1960s to the 1980s, dominating the global market with a share of around 80%. The drives consisted of slow-rotating single- or three-phase synchronous motors (without gears or belts) and were only converted to brushless DC motors in the last machines in the 1980s. This drive delivers a starting torque of 0.39 Nm / 4.0 kg cm with speed fluctuations of 0.015% WRMS.

(W-RMS stands for “weighted root-mean-square.” “Weighted” means that a filter is used here as well. RMS means that the so-called effective value is taken into account rather than the peak value. This is always lower than the peak value.)

“Synchronization errors are noticeable to the average ear at 0.2–0.3% and, above a certain level, lead to audible pitch fluctuations that are perceived as ”warbling,“ ”howling,“ or ”whining.” Hi-fi equipment allows a maximum synchronization error of 0.2%. Modern devices achieve values of around 0.02% to 0.08% thanks to quartz-controlled motors.”

The control system for the turntable drive must also be able to accommodate and process the speeds and record sizes commonly found on the market for a commercially viable cutting machine. Common speeds on the market are 33.3, 45, and 78 rpm, as well as 16.7, 22.5, 39 rpm for “half speed mastering” (where cutting is performed at half speed to achieve higher frequencies during playback). Standard record sizes are 7“, 10”, and 12“ (30 cm). For master cuts that are sent to the pressing plant, 14” records are also common. The larger the record, the more precise and stable the turntable and drive must be.

In addition, it must be manufactured accordingly to prevent “slippage” between the record and the turntable. Neumann cutting machines also used turntables with negative pressure, which sucked the record onto the turntable. Alternatively, record clamps and records with two holes (center hole and drive hole) are also used.

uses a powerful direct drive for records 7” up to 12" in the FP9. Speeds from 16.7 to 78 rpm are possible

4. CUTTER HEAD

Regardless of whether it is a mono or stereo head, the cutting head should ideally be able to transmit frequency ranges from 20Hz to 18kHz. The resonance frequencies should be as low as possible. Stereo heads should also enable good channel separation.

Two different methods were used to transmit stereo signals according to the principle presented in 45/45-type stereophonic recording (see writing process).

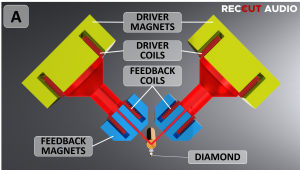

Figure A shows a cross-sectional view of the Neumann SX-74 cutting head, in which the two stereo channels are moved at an angle of ± 45 degrees to the record surface.

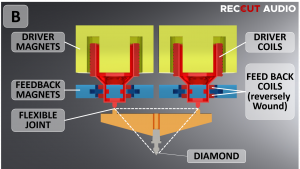

Figure B shows how the Ortofon cutting head works. An isosceles T-piece is moved by two vertical coils to implement the 45-degree groove movement of the flank recording process.

Figure A: Stereo cutting head system A: 45/45 degree principle Neumann

Figure B: Stereo cutting head system B: T-piece principle Ortofon

uses the 45°/45° principle for the CH9, as shown in Figure A. With V-spring for the torsion tube and feedback coils.

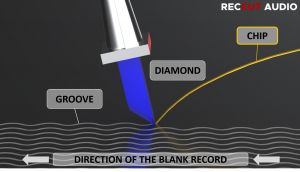

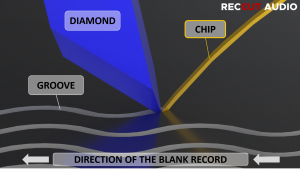

5. CUTTING CONCEPT

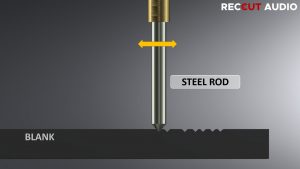

A basic distinction is made between pressing (embedding) and cutting.

5.1. Embedding

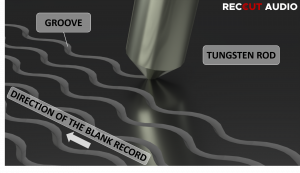

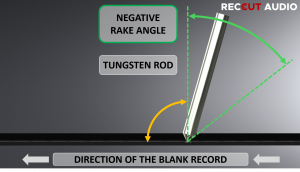

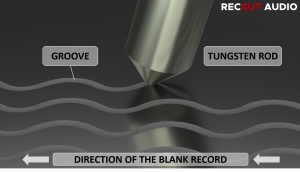

When pressing (embedding), the stylus (steel, tungsten, sapphire, or diamond needle) is pressed into the surface with the angle of the stylus in the direction of travel, i.e., it is pulled (similar to drawing a pattern in butter with a fork). The contact pressure must be higher and the quality is slightly lower (limited high frequencies). The stereo effect is also virtually non-existent. The technical implementation is simpler and no “cutting thread” is created.

Figure: Embedding (pressing) with a tungsten rod

Figure: Embedding (pressing) with diamond (or sapphire)

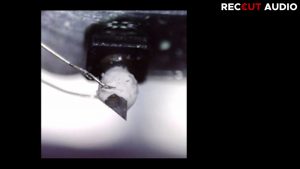

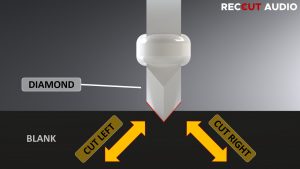

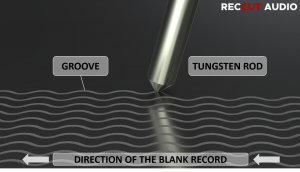

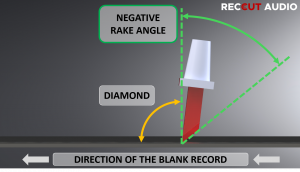

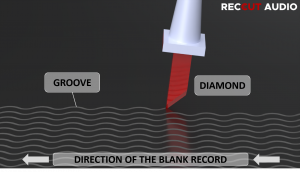

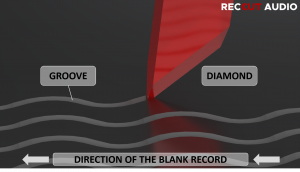

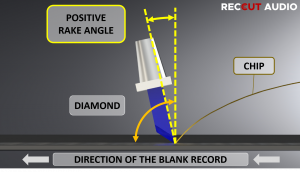

5.2. Cutting

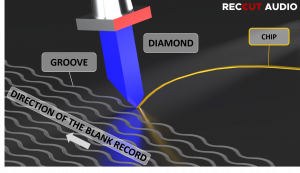

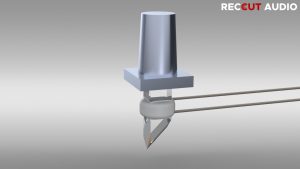

When cutting, the stylus is positioned at 90° or even up to 8° against the direction of travel (positive rake angle). This creates a “cutting thread” (chip) from the removed material. This thread must be extracted, otherwise it will get caught or come between the stylus and the plate and cause the stylus to jump. The contact pressure is lower than with embedding, which makes it easier to move the needle in the material. The quality is much higher (high frequencies and good stereo effects are possible) and cutting is done with a sapphire (in lacquer) or diamond needle (in PVC or PETG).

Figure: Cutting with diamond

uses the CUTTING principle with cutting chips for the CH9. However, embedding is also possible with adjustments

6. CUTTING STYLUS

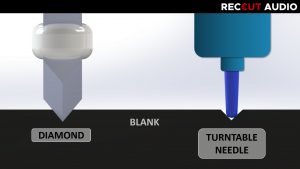

The cutting stylus is made of sapphire or diamond. Unlike pickup systems, the flanks are (straight) at a 90° angle and the tip is not rounded. (A turntable pickup needle—whether round or oval cut—scans the flanks during playback).

uses a heated diamond cutting stylus type 320 in the CH9 cutting head.

7. STYLUS PRESSURE

Similar to a turntable (tracking force), the stylus must cut or press into the record with a certain amount of pressure (stylus pressure). The pressure determines the cutting width (approx. 40µm) and depth (approx. 20µm). When no signal is being transmitted (start groove, pause between two songs, end groove), the cutting depth is reduced, which in turn must be compensated for, otherwise the needle may “jump” out of the groove during playback. Increased contact pressure can also compensate for a slightly worn stylus.

uses a variably adjustable tracking force with adjustable automation and damping on the FP9

In a heated stylus, a heating wire is wrapped around the gemstone and electricity flows through it. A heated stylus can reduce background noise (silent cut) due to the heat generated during cutting.

The heating wire begins to glow at a current flow of approximately 0.7A. It then reaches a temperature of between 500°C and 850°C!

Just as important as the stylus heating is the plate heating. A “warm” plate is better and, above all, quieter to cut. The plate temperature for PETG plates should be between 30° and 38°. The temperature also influences the “cutting thread” of the separated material. Excessively high temperatures deform the blank and cause the “cutting thread” to melt and stick together during cutting (making suction impossible). Excessively low temperatures reduce the cutting quality.

In this context, a humidity level of 50% is also desirable.

uses a variably adjustable temperature control with automatic temperature monitoring and regulation in the FP9. The heating wire of the CH9 is also adjustable and should not exceed 0.6A.

9. GROOVE SPACING and GROOVE DEPTH

One groove per side! Groove spacing refers to the distance between one groove and the next. Depending on the volume of the recording and the frequency (low frequencies require more space), in extreme cases the stylus can deviate up to 200µm in each direction (resulting in a total groove width of up to 400µm)! To ensure that the cut groove does not overlap with the groove on the following revolution, a groove spacing (feed) of approx. 420µm must be implemented (in the case of embedding, the spacing must be even greater because some material is pressed into the groove of the previous groove during pressing).

9.1. Constant groove spacing

With a constant groove spacing (420µm), the time for music would soon be up (at 33.3 rpm, max. 6 minutes). If you cut more quietly and with less bass (e.g., from 40Hz), you can theoretically cut up to 22 minutes of music.

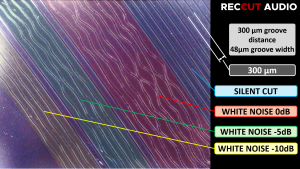

The figure shows the cutting of a signal with a constant feed rate of 300µm/revolution. Different volumes during cutting show the different “deflections” of the groove (the groove width itself is relatively constant at 48µm).

Image: Cut white noise signal at a constant feed rate of 300µm/rev and different volumes

9.2. Variable Pitch Recording

With variable groove spacing, the “feed rate” changes depending on the recording volume and frequency. The feed rate is reduced to 80µm for quiet passages and increased to 400µm for loud passages. This allows for longer recording times even with “loud” cuts. However, it is a very complex process, as ideally the music signal must be available half a record rotation (0.9 seconds at 33 rpm) before the cut as a preview signal.

In any case, the feed must not be carried out in a “jerky” manner, as sudden changes of 1µm would already produce an audible sound. High-precision drive spindles are used for this purpose.

Variable feed and depth control optimize playing time and level capability for longer LPs through the efficient use of space on the record. Essentially, the grooves become narrower and closer together at low signal levels, while they become deeper and further apart at higher signal levels.

The necessary calculations for groove spacing are based on three factors:

Local position (radius) of the inner groove wall (left channel). The information is stored for one revolution so that the outer groove wall (right channel) does not touch the following groove.

Local position (radius) of the outer groove wall (right channel). The future position is calculated based on the preview signal of the right channel.

Feed change as a result of low frequencies. Since low frequencies require a deeper vertical cut (more space), the stereo preview signal is used to calculate the space required.

The following figure shows the image of the grooves in relation to each other:

Figure: Variable groove control

uses both fixed and variable groove spacing control in the FP9. With fixed groove control, the groove spacing can be finely adjusted from 70µm to 400µm. With variable groove spacing control, limit values can be set. This then works with a separate input for the pre-signal.

The aforementioned “cutting chip,” which is produced from the removed material, must be suctioned via a suction pipe (then a hose) directly next to the cutting stylus. This is best achieved using a high-performance rotary pump.

Static charges make it difficult for suction to remove the chips. These are caused by cutting the carbon-containing diamond on the plastic record blank. This can be reduced by applying antistatic material to the blank records. Excessive (or insufficient) humidity also increases electrostatic problems. Therefore, the humidity should be 50% during cutting.

Image: Rotary pump - side channel compressor

Piston pumps would generate a pulsating air flow, which in turn (due to its proximity to the cutting stylus) would move the stylus back and forth, which in turn would be audible during playback. A high-performance rotary pump generates a steady air flow and does not overheat. The “cutting thread” must be collected in a container upstream of the pump, as it would damage the pump over time.

Image: Reccut Audio SU9 Suction Unit

uses a side channel compressor in the SU9. This can be controlled manually or automatically via the FP9 main unit.

11. AUDIO SIGNAL PROCESSING

11.1. IRIAA EQUALIZER

If a piece of music were to be cut without filtering, low frequencies (20-400Hz) would be reproduced much too loudly and high frequencies (above 5kHz) would be almost inaudible. This is because 10W of a signal at 100Hz can move the drive coil (like a loudspeaker) and thus the cutting stylus slowly and strongly. 10W of a signal at 5,000Hz moves the cutting stylus quickly but with hardly any noticeable deflection. (This has to do with the ratio of frequency and amplitude).

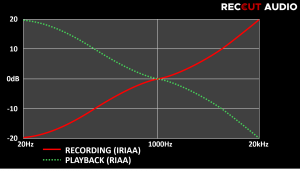

For this reason, the IRIAA (inverse RIAA equalization curve) cutting characteristic was established in the 1960s.

This attenuates low frequencies and amplifies high frequencies. (Phono amplifiers are equipped with RIAA equalizers for playback, which amplify the low frequencies and attenuate the high frequencies to the same extent when playing the record.)

Figure: IRIAA equalizer characteristic curve for recording (red) and RIAA equalizer characteristic curve for playback (green)

11.2. HIGH-PASS AND LOW-PASS FILTERS

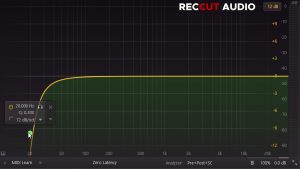

A high-pass filter allows “high” frequencies to pass through. Since these filters are used in the audio range to cut off a frequency band below a range of, for example, 20Hz (i.e., allowing frequencies above 20Hz to pass through), they are also called low-cut filters. When cutting records, frequencies that are too low should be avoided. This is because they take up “a lot of space” and, in extreme cases, can cause the needle to jump out of the groove during playback.

Figure: Low-cut filter (20Hz -72dB); FAB Filter Plug-In (in the DAW)

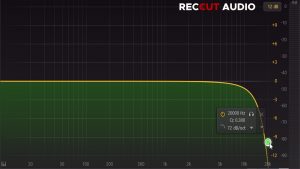

A low-pass filter allows “low” frequencies to pass. Since these filters are used in the audio range to cut off a frequency band above a range of, for example, 20kHz (i.e., allowing frequencies up to 20kHz to pass), they are also called high-cut filters. When cutting records, frequencies that are too high should be avoided because they place extreme strain on the cutting head (coils can burn out).

This is caused by the strong amplification of the IRIAA characteristic curve, which is amplified by +20dB at 20kHz. Up to 300W can then be applied to the 20W coil of the cutting head (if the amplifier has the power). At 10kHz, “only” +13dB is amplified.

A high-cut filter should be set between 14kHz and 18kHz for record cutting.

Figure: High-cut filter (20kHz -72dB); FAB filter plug-in (in the DAW)

The FP9 main unit has an analog 18kHz high-cut filter with -80dB (Butterworth 4th order) at the audio input.

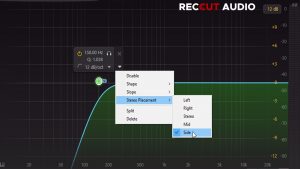

11.3. ELLIPTIC EQUALIZER (EEQ)

This equalizer is only needed for stereo cuts. Since music tracks in the very low frequency range in stereo can cause the left and right channels to play the bass out of phase, this would also be cut in this way. The problem arises during playback, because the needle can then jump out of the groove. Therefore, care must be taken during cutting to ensure that this does not happen. This is why the EEQ is used. It “monoizes” low frequencies and should definitely be used for record cutting. From the selected frequency onwards, it should reproduce stereo signals without distortion.

Figure: EEQ; 150Hz; FAB Filter Plug-In (in the DAW)

Implementation via external elliptic equalizer or plug-in (in the DAW)

11.4. PARAMETRIC EQUALIZER

Similar to a graphic equalizer, it boosts certain frequencies and cuts others. However, it does not do this with one control per frequency range as with a graphic equalizer. The parametric EQ basically has three controls:

FREQUENCY: This control continuously selects the frequency range (e.g., 550Hz).

GAIN: This control continuously selects the gain or attenuation of the frequency (e.g., +4.5dB).

Q: This control continuously selects the frequency bandwidth “Q” – i.e., how ‘sharp’ or “flat” the frequency response should be. For example, with a Q=15, only a range of 0.1 octaves is affected (sharp), whereas a Q=0.5 covers approximately 2.5 octaves (flat).

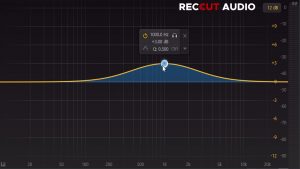

Figure A: Parametric EQ 1000Hz; +3dB; Q=1; FAB Filter Plug-In (in the DAW)

Figure B: Parametric EQ 1000Hz; +3dB; Q=0.5; FAB Filter Plug-In (in the DAW)

Figure C: Parametric EQ 1000Hz; +3dB; Q=10; FAB Filter Plug-In (in the DAW)

Typically, a parametric equalizer does not consist of just one unit, but of several elements for use in different frequency ranges (four to six units). This allows extreme distortion characteristics to be created.

This serves to compensate for the resonance curves of the cutterhead, but also to master your own music cuts. This allows you to cut with more bass, midrange, or treble.

Figure: Signal distortion caused by five parametric EQs; FAB filter plug-in (in the DAW)

Implementation via external graphic equalizer, parametric equalizer, or plug-in (in the DAW)

provides a preset setting for FAB filters for the CH9 cutting head to ensure good sound quality.

11.5. FEEDBACK COIL EQUALIZER

Modern cutting heads have feedback coils (one per channel). The movement of the drive rods (which are fed by the signal) is measured via the feedback coils. This allows the “original” music signal and the feedback coil signal to be compared, differences to be adjusted, and resonances to be compensated. This results in “clean” resonance-compensated cutting.

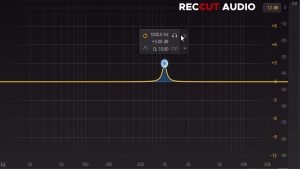

Image: RECCUT AUDIO - FBCA-9-AMPLIFIER signal connections on the backside

The FP9 main unit already includes an analog stereo feedback compensation amplifier (FBCA) with adjustable gain and attenuation. An external FBCA Amplifier from RECCUT AUDIO is also available for the CH9 (for use of the CH9 with other lathes).

11.6. LIMITER

A limiter is a dynamic processing effect device in a rig or a plug-in that reduces the output level (amplitude of the audio signal voltage) to a specific value. This is determined by the “limiter threshold.” This prevents clipping during cutting.

Figure: FAB Filter Plug-In (in the DAW)

How it works: An extreme form of compressor – acts very quickly and harshly, often with a ratio of 10:1 or ∞:1.

Purpose:

Prevents peaks from exceeding a certain limit.

Acts more like a “safety brake.”

Use in vinyl mastering:

Protection against overloading the cutting system.

Prevents the groove from becoming too distorted (otherwise the needle will skip).

Serves primarily for technical safety, less for musical design.

Implementation via external limiter or plug-in (in the DAW)

11.7. COMPRESSOR

A compressor in vinyl mastering (and also in audio mastering in general) is not used directly to “amplify” or “attenuate” in the sense of a volume control, but rather for dynamic processing.

There are technical limitations when cutting a vinyl record:

Peaks (transients) that are too loud can cause the needle to jump out of the groove or require the groove to be cut too wide.

Excessive dynamics (i.e., a large difference between quiet and loud passages) can be problematic because quiet passages are drowned out by noise and loud passages exceed the physical limits of the medium.

The compressor therefore has the following tasks in vinyl mastering:

Limiting peaks – excessive transients are intercepted so that the cutting system and the needle are not overloaded.

Compressing the signal – quiet and loud passages are brought closer together. This makes the music on the record more evenly audible, even at normal playback volume.

Enabling greater overall volume – when peaks are controlled, the entire track can be played louder without causing overload or needle problems.

In short:

The compressor is used in vinyl mastering to tame the dynamics and enable a stable, technically playable, and sonically consistent pressing.

In summary

Compressor = tool for creatively controlling dynamics and shaping sound.

Limiter = tool for technically preventing anything from “going over the edge.”

Figure: FAB-FILTER PLUG IN (IN THE DAW): MB COMPRESSOR

Implementation via external compressor or plug-in (in the DAW)

11.8. DE-ESSER

A De-Esser prevents harsh sibilant sounds in the voice (such as “S” or “SCH”). The problem of sibilance usually arises from “imperfect” mastering. For aesthetic reasons, high frequency ranges (approx. 7 kHz to 11 kHz) are often boosted during mastering to give the voice more presence, resulting in these disproportionately amplified effects. These effects are usually exacerbated by the use of a “compressor.” The IRIAA EQ characteristic curve used further amplifies the effect. The use of a de-esser is unavoidable in “imperfect” mastering of music recordings. First, frequency ranges are separated, sections that are too loud in the mid and upper frequency ranges are compressed, and then the separated frequency ranges are recombined.

Figure: FAB-FILTER PLUG IN (IN THE DAW): De-Esser compresses sections that are too loud

Technically speaking, a de-esser is a specialized form of compressor – not a limiter.

Why?

A de-esser works on a frequency-dependent basis:

It detects sibilant sounds (S sounds, sharp “T” and “Sh”), usually in the 5–10 kHz range.

As soon as these frequencies exceed a certain threshold, it reduces only this range in level.

The functionality is therefore identical to that of a compressor:

Threshold, ratio, attack, release – only applied to a limited frequency band.

Comparison:

Compressor: Regulates level ratios across a wide band or, if desired, with sidechain.

De-esser: Compressor that specifically attenuates a frequency band (S sounds).

Limiter: Rigorously cuts off all level peaks.

Implementation via external De-Esser or plug-in (in the DAW)

The higher the quality of the amplifier, the higher the quality of the cut. The special feature of an amplifier for record cutting is that it requires high power and can provide this high power quickly (without time delay). Although the coils in the cutterhead only have 10W, 20W, or 40W speaker coils, the power amplifier requires about 300W.

If a speaker reproduces, for example, 15W of its power at 1kHz, it also requires twice the power at double the frequency. So at 2kHz, about 30W; at 4kHz it needs about 60W; at 8kHz it needs about 120W and at 16kHz it needs about 240W! Consequently, about 300W is required for 20kHz.

Of course, 300W is a very high load for a 15W loudspeaker, even if it is only applied for a very short time, which causes the loudspeaker to heat up considerably. The Neumann cutting machines in the 1980s had helium cooling for the loudspeakers in order to be able to cut at 18kHz (up to a maximum of 20kHz) (and were at their limits). Therefore, cutting is usually “only” done up to 14kHz (16kHz).

13. PRODUCTION OF INDIVIDUAL PIECES AND SMALL SERIES

For small series (approx. 1-100 pieces), the blank record is cut in real time (sides A and B) and the cut record can be played directly on a turntable.

Lacquer-coated records are not suitable for this purpose as their surface is too soft. The turntable needle would destroy the record after just a few plays, and the playback needle would also stick to the lacquer surface and be destroyed.

After the devastating fire at the Apollo factory, the manufacturer of 80% of the world’s lacquer blanks, these blanks are difficult to obtain and relatively expensive.

In addition, lacquer blanks would also be uneconomical for direct cutting because only one side can be played.

Therefore, PETG or PVC plastic is used for cutting.

The advantages are the cost (approximately two to five euros per piece, depending on the size) and a durability similar to that of vinyl records. (Special shapes and colors are slightly more expensive).

The disadvantage is that the higher hardness of the plastic makes it much more complex and difficult to cut. Due to the surface hardness, more effective suction of the harder (and statically charged) cutting thread is necessary. A harder and more expensive diamond stylus is also required instead of a sapphire stylus. Static charges caused by diamond styluses are more difficult to avoid. The silent areas are slightly louder than with lacquer cuts and pressed vinyl records.

can produce individual items and small series with the FP9

14. LARGE-SCALE PRODUCTION

For large-scale production, a record pressing plant is the only economically viable option. The large-scale production of records is very complex and is still carried out today in exactly the same way as it was 60 years ago.

The process is divided into the following steps

14.1. Production of a lacquer blank

A special lacquer coating is applied to one side of a thin aluminum plate. The surface is completely smooth. The blank has a center hole and a second hole for cutting machines equipped with a drive mandrel.

14.2. Production of the master disc

In the cutting studio, the audio signal is processed and cut into the blank using a stylus on a record cutter. Since only one side of the lacquer blank can be used, a second blank is cut for the B-side of the record. A master cutter then visually and acoustically inspects the blank and manually corrects any defects using very sharp tools under a microscope.

can produce lacquer blank cuts with the FP9. To do this, the diamond stylus must be replaced with a sapphire stylus.

14.3. Electroplating the master

Since the surface of the lacquer blank is not conductive, a thin layer of silver is applied and cleaned. The master, which acts as a cathode, is then placed in a nickel bath for electroplating. This forms a thin layer of nickel on the groove surface. After separating the nickel foil from the master, the so-called father impression of the master is obtained. This process must be carried out for both blanks (side A and B). Afterwards, the lacquer blank is unusable for further impressions. Theoretically, records could already be pressed with the father mold. However, since such a mold is only suitable for a maximum of 400 record pressings (due to quality losses), several molds must be produced.

14.4. Molding by electroplating

Further electroplating processes must follow in order to obtain a sufficient number of pressing matrices for 4000 records (typical print run for an average music album). Accordingly, a female mold (or several female molds for print runs of more than 4000) is electroplated from the male mold using the same principle. The mother mold is then again a positive mold like the master disc.

To obtain a negative mold, several sons are again produced electrolytically using the same process. Each of these sons can press about 400 records without loss.

14.5. Pressing vinyl records

Once the vinyl granulate has been heated to form a viscous mass, it is molded into small pucks (roughly the size of a hockey puck). The high-performance press is loaded with the sons, with the matrices for sides A and B placed on the top and bottom of the press plates. The vinyl puck is then placed in the press. The record labels, made of special paper, are also placed in the center of the press. The vinyl is pressed into a record at a high temperature of around 150 degrees Celsius and a pressure of at least 200 bar. Finally, the pressed record is quickly cooled in the press and the edges are trimmed by a cutting tool.

The records are then placed in sleeves and covers and packaged for delivery.

14.6. DMM (Direct Metal Mastering) in copper discs

The DMM process was introduced in the 1980s. Special record cutting machines are used to cut into copper blanks instead of lacquer. The big advantage is the shortened manufacturing process. The numerous savings in the electroplating process are an advantage. Since eight to ten negative molds can be produced from a copper blank without loss, most orders can be fulfilled with a copper blank.

cannot cut copper with the CH9. This requires a special process and a different cutting head design.

14.7. Savings in the manufacturing process thanks to DMM blanks

Since copper is already conductive, it is no longer necessary to apply a silver layer. The manufacturing steps for master and mother matrices are also eliminated. This means that the sons can be produced directly in the electroplating bath.

The rest of the process is identical to that described above.

15. DAW (Digital Audio Workstation)

DAW stands for Digital Audio Workstation. It is software that allows you to produce, edit, record, mix, and master music—basically everything related to music production on a computer.

15.1. What do you need a DAW for?

A DAW is the central tool for music producers, sound engineers, and composers. You need it for things like:

- Recording Recording audio – e.g., vocals, instruments, or podcasts

- Composition Writing music with MIDI (control virtual instruments)

- Editing Cutting, moving, and correcting audio & MIDI

- Mixing Adjusting volume, effects, panorama, etc.

- Mastering Final sound editing for release

- Building beats Using samples, loops, and virtual drums

15.2. Examples of well-known DAWs

Ableton Live

Strengths : Intuitive loop-based workflow, great for live performances, lots of creative tools

Weaknesses: Classic audio editing features less in-depth

Suitable for: Electronic music, live acts, DJs

FL Studio

Strengths : Very beginner-friendly, strong for beatmaking & electronic genres, many plugins

Weaknesses: Less popular for recording & complex audio workflows

Suitable for: Hip-hop, EDM, beginners, beatmakers

Logic Pro

Strengths : Extensive sounds & plugins, good MIDI/audio integration, reasonably priced

Weaknesses: Only available for macOS

Suitable for: Songwriting, producers, composers

Cubase

Strengths : Very strong in MIDI, orchestration & film scoring, extensive features

Weaknesses: Somewhat complex, relatively expensive

Suitable for: Composers, film/TV, professional studios

Cubase Pro 10

Strengths : Highly professional version with advanced mixer, audio alignment & score editor

Weaknesses: Expensive, complex learning curve

Suitable for: High-end studios, film music, professionals

Pro Tools

Strengths : Industry standard for recording & mixing, very reliable

Weaknesses: Expensive, steep learning curve, less creatively oriented

Suitable for: Recording studios, mixing & mastering engineers

Studio One

Strengths : Modern workflow, drag & drop, fast operation, all-rounder

Weaknesses: Less third-party support than older DAWs

Suitable for: All-rounders, home studios, modern producers

Bitwig Studio

Strengths : Innovative sound design, modular structure, great for experimentation

Weaknesses: Not yet widely used, small community in some cases

Suitable for: Sound designers, experimental music

Reason

Strengths : Creative “rack” concept, many proprietary instruments, flexible

Weaknesses: Workflow sometimes cumbersome, less recording-oriented

Suitable for: Electronic music, sound design

Reaper

Strengths : Very affordable, extremely customizable, runs even on weak hardware

Weaknesses: Interface seems raw, lots of setup required

Suitable for: Home studio, indie producers, audio engineers

Audacity

Strengths : Free, very lightweight, great for quick recordings & audio editing

Weaknesses: No MIDI support, limited mixing/mastering functions

Suitable for: Beginners, podcasters, quick audio edits

Cakewalk (by BandLab)

Strengths : Full-featured, free DAW, good MIDI & audio features, ProChannel mixing

Weaknesses: Only available for Windows, smaller community

Suitable for: Windows users, beginners with professional ambitions

15.3. Why is a DAW so important?

Because it offers all the tools that used to be found in expensive recording studios—today, you can do it all on your own laptop, often even with free programs (such as Cakewalk, Tracktion, LMMS, GarageBand, etc.).

15.4. DAW plugins

Plugins for a DAW are additional programs that you use within the DAW to expand, modify, or create sound.

Think of your DAW as a recording studio—plugins are the devices you put in your studio, such as virtual synthesizers, effects, equalizers, or compressors.

Types of plugins

There are two main types:

- Instrument plugins (VSTi / AU Instruments / AAX Instruments). These generate sound – e.g., virtual pianos, synthesizers, drums.

- Effect plugins (VST / AU / AAX Effects). These modify the sound of audio tracks or instruments.

Examples:

- EQ (Equalizer) Make certain frequencies louder/quieter

- Compressor Even out volume differences

- Limiter Limit the level to prevent clipping

- Reverb Add spatiality/reverb

- Delay Create echo effects

- Distortion/Saturation Make the sound “gritty” or “warmer”

How do you get plugins?

Your DAW often comes with many plugins already included

There are free plugins (e.g., from Spitfire Audio, Valhalla, TAL, Kilohearts, and many more)

Commercial plugins are often more powerful or specialized (e.g., from FabFilter, iZotope, Native Instruments, Waves)

Why do you need plugins?

- To create better sounds

- To have more control over the mix

- To make creative sound distortions

- To customize your workflow

can produce individual items and small series with the FP9

16. DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter)

A DAC converts digital audio data (e.g., MP3, WAV, FLAC) into an analog signal that can be heard through speakers, headphones, or amplifiers.

16.1. Why do you need a DAC?

Digital music (e.g., from your PC, smartphone, music player) consists of binary data (0 and 1).

But:

Speakers and headphones need an analog signal to produce sound.

Therefore, every playback device needs a DAC to make music audible.

16.2. When is an external DAC worthwhile?

An external DAC can be useful if you:

- Want better sound than the built-in DAC of your PC or smartphone

- Use high-quality headphones that are sensitive to interference or poor signal quality

- Want to listen to high-resolution audio (Hi-Res)

- Produce music and depend on precise sound reproduction

16.3. Differences between simple and high-quality DACs:

Simple DAC (e.g., in a laptop):

- May produce noise or distortion

- Limited audio quality

- Inexpensive, but often mediocre

High-quality external DAC

- Very clean sound reproduction

- Supports high-resolution audio

- More expensive, but significantly better

16.4. DAC vs. Audio interface

A DAC is often only responsible for playback.

An audio interface usually has a DAC + ADC (analog-to-digital converter) – making it suitable for both recording AND playback.

16.5. Conclusion:

A DAC is essential for making digital music audible.

Most devices have one built in, but if sound quality is important to you, it’s worth investing in a high-quality external DAC.

17. AUDIO INTERFACE

An audio interface is an external device that serves as a link between your computer and professional audio hardware—i.e., microphones, instruments, studio monitors, or headphones.

17.1. What do you need an audio interface for?

An audio interface is used to:

Record audio to your computer

e.g., connect microphones or electric guitars

Convert analog signals into digital data (ADC – Analog to Digital Converter)

Play back audio from your computer in high quality

- e.g., to headphones or studio monitors

- Convert digital data back into analog signals (DAC – Digital to Analog Converter)

17.2. What can an audio interface do that a PC cannot?

Standard PC or laptop

- Built-in sound card with rather basic quality

- Usually only micro jack as input

- Hardly suitable for music production

- High latency during recording

Audio interface

- High-quality converters for better recording and playback quality

- XLR, jack, MIDI, line-in/out, etc.

- Specially designed for musicians, producers, podcasters, etc.

- Low latency, e.g., for real-time monitoring

17.3. What does an audio interface have?

A typical interface has:

- XLR inputs for microphones

- Jack inputs for instruments (guitar, keyboard)

- Headphone output

- Line outputs for studio monitors

- Phantom power (48V) for condenser microphones

- Gain controls for volume control during recording

- USB / Thunderbolt / Audio over IP for connection to a computer

17.4. Who needs an audio interface?

Musicians & producers: To record vocals, instruments, or beats in professional quality

Podcasters & streamers: For clear microphone sound & live monitoring

Sound engineers & sound designers: For precise mixing, recording, and editing

MIDI users (e.g., keyboard players): Many interfaces also offer MIDI inputs and outputs

17.5. Audio interface ≠ sound card

A sound card is internal (built into the PC) and often limited to simple playback.

An audio interface is external, significantly higher quality, and offers many more connections and functions for professional audio work.

17.6. Conclusion:

You need an audio interface if you want to record professionally or listen to high-quality audio—whether you’re making music, podcasting, or adding sound to videos.

It’s essentially the heart of every home or project studio.

18. SIGNAL PATHWAYS

The signal pathway from the musician to the record involves many technical and creative steps—from the first note in the studio to the physical cut on the record.

Here is a simplified explanation of the complete signal path in logical order:

18.1. Musician plays/sings in the studio

The musician produces acoustic sound waves, e.g. with their voice, guitar, drums, or other instruments.

18.2. Microphone picks up the acoustic signal

The microphone converts sound into an analog electrical signal.

With electric guitars or synthesizers, the signal can also come directly as electrical voltage via jack cables (DI signal).

18.3. Preamp (microphone preamplifier)

The electrical microphone signal is very weak.

The preamp (in the audio interface or mixing console) amplifies it to a usable level (line level).

18.4. Analog signal is processed (optional)

Optional routing through analog effects:

- EQs

- Compressors

- Reverbs (reverb units)

- Limiters

Or forwarded to external devices via patchbay.

18.5. Analog-to-digital conversion (ADC) → Recording in DAW

The analog signal is converted into a digital signal (binary data) in the audio interface or AD converter.

The DAW (digital audio workstation) records the audio data (e.g., Pro Tools, Cubase, Logic).

18.6. Editing & mixing in the DAW

Editing: Cutting, correcting, tuning (e.g., Autotune)

Mixing: All tracks are balanced in terms of sound: Volume, panorama (stereo), effects (delay, reverb), EQ, dynamic processing

Result: Stereo mixdown (often as a WAV file)

18.7. Mastering

The finished mix is optimized sonically so that it:

- sounds good on all playback systems,

- is loud enough (loudness adjustment),

- is consistent with other songs,

- meets technical specifications (for vinyl, streaming, etc.).

Result: mastered stereo file – e.g., 24-bit/96 kHz WAV

18.8. Mastering for vinyl records

Mastering for vinyl records has some distinct characteristics that result directly from the physical properties of the medium.

These characteristics relate to frequencies, dynamics, stereo image, volume, and playing time.

Special features of mastering for vinyl records:

Lower loudness

- Vinyl records cannot tolerate extremely loud masters as used in streaming.

- Too high a level = wider groove, which allows for less playing time or even causes distortion.

- Goal: Balanced volume, not maximum.

Bass must be in mono

- Low frequencies (< 150 Hz) must be centered (mono).

- Reason: Low stereo bass causes lateral needle movement → can cause the needle to skip.

- Solution: Bass mono summing or mid/side processing in mastering (EEQ elliptical equalizer).

Avoid phase problems in the low bass

- Out-of-phase bass (e.g., due to reverb, stereo effects) can cause unstable grooves.

- Check using phase analysis or vinyl-specific plugins (e.g., bx_control V2, VUMT deluxe, etc.).

No exaggerated highs/sibilants

- Sharp “S” sounds (sibilance) or aggressive hi-hats can hiss, distort, or deflect the needle on vinyl.

- Solution: Use de-essing or attenuation above 8–10 kHz.

Limited playing time per side of the record

The longer the side, the quieter and with less bass it must be cut.

Guidelines:

- 12″ LP at 33 rpm: approx. 18–22 minutes per side at a good level

- 7″ single at 45 rpm: approx. 4–6 minutes per side

Too much content = loss of quality or unplayable record

Less compression/limiting

Vinyl loves dynamics – too much brickwall limiting can:

- Cause cutting problems

- Make the material sound “squashed”

Ideally: gentle compression, no extreme loudness values (as with streaming)

Deliver special master file

Recommended format:

- 24-bit WAV

- 1–96 kHz

- No dither, no limiter clipping

Headroom of approx. -3 dBFS for the cutting technician is standard

Pay attention to the order of the songs

Inner grooves (last tracks on a side) sound worse due to lower resolution. Therefore:

- Loud/complex tracks towards the outside

- Quiet/softer songs towards the inside

Mastering is often adjusted for vinyl

Some artists make their own vinyl master, which differs from the streaming master.

It is deliberately less loud, less compressed, and mastered more for stability.

18.9. Digital-to-analog conversion (DAC) for cutting

Before the record is cut, the digital master must be converted back into an analog signal.

This is done using a high-quality DAC, often in the master cutter’s studio.

18.10. Cutting amplifier & cutter head (mastering lathe)

- The analog signal is forwarded to the cutting amplifier.

- This controls the cutting head, which cuts vibrations into a lacquer disc.

- This is the physical cutting of the audio data into a spiral groove – the first master of the record.

18.11. Closed Loop in Feedback Cutterheads

The closed-loop system in a feedback cutterhead (a cutting head with feedback coils) is a central component of modern vinyl record production with high sound quality. A corresponding feedback compensation amplifier is required for this.

What is a feedback cutterhead?

A cutterhead is the part of the cutting system that cuts the groove into the lacquer disc – in other words, the “heart” of vinyl mastering.

A feedback cutterhead uses a closed-loop system to make the cutting process more controlled and precise.

Basic principle: Closed loop / feedback

The problem with open systems (open loop):

- With pure “drive-only” (open-loop) cutterheads, the audio signal is sent to the coils that move the cutting needle.

- However, there is no control over how precisely the needle actually moves.

- Result: Nonlinearities, distortions, reduced precision.

Solution: Feedback system (closed loop)

A feedback cutterhead uses additional coils (sensor coils) to measure the actual movement of the cutting needle. The adjustment is made in a feedback compensation amplifier (FBCA-Amplifier). This is called electromechanical feedback.

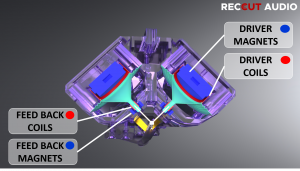

Figure:: RECCUT AUDIO - CH9-CUTTERHEAD X-Ray picture with Driver and Feedback coils

The components of the feedback cutterhead:

- Drive coils: Convert audio signals into mechanical movement

- Cutting stylus: Cuts grooves into the lacquer disc

- Sensor coils: Measure the actual movement of the stylus

Cutterhead CH9 is a Feedback cutterhead for closed loop.

The components of the feedback cutterhead:

- Drive coils: Convert audio signals into mechanical movement

- Cutting stylus: Cuts grooves into the lacquer film

- Sensor coils: Measure the actual movement of the stylus

- Feedback loop: Compares the desired and actual movement and corrects errors

- Amplifier control loop: Responds to feedback and adjusts the signal

The closed-loop amplifier (feedback compensation amplifier)

A closed-loop amplifier (also known as a feedback cutting amplifier) for a feedback cutterhead has special inputs and outputs for sending the audio signal to the cutterhead and processing the feedback signal from the cutterhead.

This distinguishes it significantly from a “normal” amplifier.

Typical connections of a closed-loop amplifier for vinyl cutting systems:

- Audio input (Line In / Audio In): Input for the master audio signal (e.g., from the DAC or DAW output).

- Drive outputs (Cutting Head Drive / Voice Coil Out): Amplified signals for the drive coils of the cutterhead. Usually 2 channels: left and right.

- Feedback inputs (Feedback Coil In / Sense In): Inputs for the feedback signal from the sensor coils in the cutter head (measurement of the needle movement).

- Power connection (power supply): High-quality, stable power supply (sometimes external PSU).

- Ground / Chassis Ground: Common ground connection – important for avoiding ground loops.

- Technical adjustment connections (depending on model): e.g. for gain, filter, calibration, offset, or balance – some can be adjusted internally or via DIP switches.

The FP9 main unit already includes an analog stereo feedback compensation amplifier (FBCA) with adjustable gain and attenuation. An external FBCA Amplifier from RECCUT AUDIO is also available for the CH9 (for use of the CH9 with other lathes).

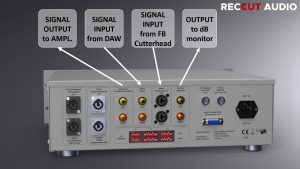

How does the feedback principle work?

LR Flowchart

A [Audio input signal] –> B [Audio signal input at the feedback amplifier]

C [Audio signal output at the feedback amplifier] –> D [Audio signal input at the power amplifier]

D [Audio signal output at the power amplifier] –> E [Drive coils in the cutterhead]

[Sensor coils in the cutterhead measure movement]

F [Feedback coils in the cutterhead] –> G [Feedback input at the feedback amplifier]

[Comparison with original signal in the FBCA amplifier] : Closed loop:

(C [Audio signal output at the feedback Amplifier] –> D [Audio signal input on the power amplifier]

External Monitoring:

C [Monitor signal output on the feedback amplifier] –> H [Audio signal input on the dB meter]

Figure: Flowchart

- Lower distortion: The needle movement is precisely controlled

- Higher precision: The cutting head corrects itself in the event of even the slightest deviations

- Better frequency response, especially in the bass range

- Greater clarity and detail, especially in quiet passages

- Consistent cut: Ideal for high-fidelity pressings

Summary:

A feedback cutterhead uses a closed-loop system in which the actual movement of the cutting stylus is measured and fed back.

This corrects deviations, resulting in a cleaner, less distorted, and more accurate groove cut.

18.12. From lacquer disc to pressed record

With direct cutting, the following steps are omitted:

- The lacquer foil is electroplated to form a master.

- This master serves as a mold for pressing vinyl records.

18.13. Summary overview:

Musician

→ Microphone

→ Preamp

→ (possibly) analog effects

→ ADC – Analog-to-digital converter

→ DAW – Recording & mixing

→ Mastering

→ DAC – Digital-to-analog converter

→ Cutting head amplifier

→ Closed-loop amplifier

→ Cutting head cuts groove

→ Direct cut, finished record

When producing at a record pressing plant, the following areas are added:

→ Lacquer disc

→ Electroplating & pressing plant

→ Finished record